Rutgers scientist uncovers further evidence that perilipin hinders fat metabolism

Findings could lead to development of new anti-obesity drugs

Earlier this month, researchers from Baylor College of Medicine (Houston) reported that mice lacking perilipin, a protein found in fat cells, had less body fat than normal mice, and that these mice could eat a high-fat diet without becoming obese (see related article). Now, Dawn Brasaemle, a nutritional sciences professor at Rutgers University's Cook College (New Brunswick, NJ), describes how perilipin acts to retain fat in humans and other animals. Her research is published in the December 8 issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Perilipin was discovered in 1990 by NIH scientist Constantine Londos, who hired Brasaemle, an expert on lipid metabolism, to investigate the protein at his laboratory. According to Brasaemle, the discovery of perilipin was important because the largest supply of energy that anybody has is stored as fat in lipid droplets in fat cells, and perilipins are the major proteins on the surfaces of these structures.

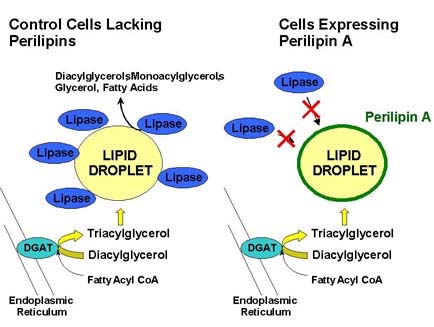

In her current research, Brasaemle, now a professor at Cook College, inserted perilipin into cells that normally don't contain it. She found that this caused the cells to store much more fat.

"Once we found out that the cells had a lot more fat, we asked why," Brasaemle says. "The answer was that the protein made the fat stay in the cells longer."

In a study reported earlier this month, Baylor scientists removed perilipin from fat cells and compared these altered cells to normal fat cells. They found that fat is broken down faster in the perilipen-free fat cells than in normal fat cells.

"So the completely different strategy led to the same idea, which is that the function of the protein is to protect fat from breakdown. If the cells have it, they don't break down fat quickly, and they store it," Brasaemle says.

According to Brasaemle, drugs developed to target perilipin would have advantages over current therapies because they would directly affect fat cells. "Some of the weight control drugs that are being researched affect messages to the brain to stop eating," she explains. "These haven't worked that well because there are also behavioral and metabolic factors involved. But a perilipin target drug could directly alter the storage and metabolism of fat."

Next up for Brasaemle: finding a way to use perilipin to combat obesity. "The options are to either figure out how to make animals produce less of it or to figure out how to alter the protein's function so that cells will selectively burn up more of the fat," she says.

For more information, contact Dawn Brasaemle at brasaemle@aesop.rutgers.edu.

Edited by Jim Pomager

Assistant Editor, Bioresearch Online